Mission Statement:

"To advance through research, education and symposia, an increased public awareness of the Cape Fear region's unique history."

Wilmington to Canada:

Blockade Runners & Secret Agents

Cape Fear Historical Institute Papers

Overview:

The port of Wilmington during the War Between the States

was a vital link that provided arms, munitions and

foodstuffs for the fledgling Confederacy.

During North Carolina’s second bid for independence,

Wilmington became the main loading point for government

cotton exports and the importation of supplies, despite

the Northern blockade, until its fall on January 16, 1865.

To illustrate the importance of Wilmington to the Southern

war effort and the immense volume of commercial traffic

of its port by 1864, Secretary of War Judah P. Benjamin

estimated that the annualized 1863 exports from the

city were $21 million, almost five times the total foreign

commerce of the entire State of North Carolina

just five years earlier.”

This vital link was important and long-lasting enough for

General U.S. Grant III, President of the US Civil War

Centennial Commission in 1961, to remark “(if it) is correct

…that between October 26, 1864 and January 1865 it

was still possible for 8,632,000 lbs of meat,

1,507,000 lbs of lead, 1,933,000 lbs of saltpeter,

546,000 pairs of shoes, 316,000 blankets,

half a million pounds of coffee, 69,000 rifles, and 43

cannon to run the blockade into the port of Wilmington

alone, while cotton sufficient to pay for these

purchases was exported, it is evident that the

blockade runners made an important

contribution to the Confederate

effort to carry on.”

An Effective Southern Response to the Blockade:

The ability of the runners to thwart the blockade can be best summed

up with Northern Admiral David Porter complaining to Secretary of

the Navy Gideon Wells in December 1864 that “the new class of

blockade runners is very fast, and (they) sometimes come in and

play around our vessels; they are built entirely for speed.” This is

how, by the last quarter of 1864, 23 out of 26 ships had

successfully run the strong blockade from Wilmington.

It should be mentioned too that the success of the blockade

runners was underscored by the Southern sympathies of

England and its colonies surrounding the United States.

The English upper classes “saw in the South a genteel,

romantic way of life threatened by industrial vandals,”

and a resentment of the increasing economic power

of the US which the North symbolized---“an arrogant

and encroaching people.” Britain’s governor of the

Bahamas, Charles John Bayley, was decidedly

pro-South and Bermuda’s governor H. St. George

Ord, “… was officially neutral but privately

predisposed toward Southern activities.”

The Canadian View of The War Between the States:

Canada saw the United States in the mid-1800's as a

dangerously aggressive neighbor which would eventually

attack Canada when strong enough, and after the outbreak

of war in 1861 Colonel Garnet Wolseley of the British

army in Canada argued that Britain should grant the

Confederacy diplomatic status. He envisioned that the

division of the United States into two separate republics

would “immediately strengthen the position of

Britain’s Canadian colonies.”

Many Canadians thought that if the South wanted to go

its separate way because of cultural and political differences,

that “surely this was no different than the desire of the

Thirteen Colonies who had declared independence

from Britain in 1776.

Seen in that light, the disintegration of the union was merely

a continuation of events begun some eighty-odd years earlier.”

This understanding of the war was underscored by

Canadian newspapers referring to the great conflict

as the “American Revolution.”

Wary of a powerful US Army, Canadian Minister of

Colonial Defence, John A. McDonald increased his country's

active militia to 100,000 men, and Britain developed a well-

detailed plan to deal with an expected invasion force

coming through the traditional Hudson Valley-Lake

Champlain route. In addition to seizing forts on the US

side of the border to delay an American advance,

a British expeditionary force of 50,000 men would add

to the existing 25,000 troops at Montreal.

Also, the British fleet under Admiral Milne would attack

US warships on the high seas as well as blockade northern

ports. Had Lincoln and Seward blundered into war with Britain

at the same time they were invading the American

Confederacy and losing the merchant marine to

privateers, the United States defeat would

have been devastating.

Canadian anxiety was increased when several American

newspapers called for the annexation of Canada in

December 1864; and Hastings Doyle, commander of

British troops in the Atlantic, publicized a conversation

between Northern Generals Grant and Meade

which intimated that Canada would be attacked after

French involvement in Mexico was dispensed with.

In February 1865, Canadian Cabinet Minister D’arcy

McGee was referring to the expansionist United States

when he said: “They coveted Florida and seized it; they

coveted Louisiana and purchased it…they picked a

quarrel with Mexico which ended by their getting

California …The acquisition of Canada was the

first ambition of (America)…Is it likely to be

stopped now, when she counts her guns afloat by

thousands and her troops by the hundreds of

thousands?” Thus, Canada was sympathetic to

the South and hoped for two smaller, and less

threatening, neighbors who might leave

British North America alone.

Ease of Entry to Canada:

The port of Halifax, Nova Scotia was a familiar destination

for Confederate agents traveling to Canada, and most

would sail on a runner to Bermuda, then take passage on

the British mail ships that ran every two weeks to Halifax.

Bermuda was about 675 miles and a good 72 hours

of sailing time from Wilmington. Some runs from

Wilmington would bypass Bermuda --

in August 1864, the Old Dominion and the City of

Petersburg delivered 2,000 bales of cotton to Halifax

after a five-day sail up the coast and past blockaders.

Another runner, the Helen went to Halifax twice in late 1864.

Escaped Confederate soldiers were also passengers on

blockade runners, seven of whom booked passage

on the runner Armstrong in St. George’s Bermuda bound

for Wilmington in November 1864, after having escaped

a Yankee prison and made their way to Halifax,

Nova Scotia, then to Bermuda.

Among other commodities leaving and entering the port

on Wilmington were government officials of the Southern

Confederacy, as well as secret agents and banished

Northern peace advocates. Among the latter was Ohio

Congressman Clement Vallandigham, who was exiled to

the Confederacy for criticizing Lincoln and his pro-war

administration, sent to President Jefferson Davis in

Richmond, then to General William Whiting in Wilmington

to be put aboard the blockade runner Cornubia in

June 1863, destined for Bermuda.

From there, Vallandigham continued on to Canada,

ending up at the Clifton House Hotel in Niagara Falls

and running as a peace candidate for Ohio governor in 1863.

The Clifton House was a popular hotel situated on the edge

of the Niagara gorge at the foot of present day Clifton Hill

Road, now the site of a botanical garden. It began operation

in the 1830’s under Harmanus Crysler, and was one

of the most popular tourist hotels in Canada with many

famous visitors. According to the Lundy's Lane

Historical Society, antebellum boarders included:

"Jenny Lind, the Swedish Nightingale (who) stayed

there for three months in 1851 and sang often from

its balconies. Charles Dickens and his wife visited the

area for 10 days in the spring of 1841" and probably

stayed at the Clifton House.

"In September 1860. the Prince of Wales (later Edward VIII)

visited for five days...(and) his retinue stayed in "the little

cottages which fill the bountiful gardens at the Clifton Hotel.

The Prince visited the Clifton House during his stay and

is reported to have watched Blondin perfom his

rope-walking stunts from its colonnades."

Another guest at the Clifton House was Floride Clemson,

the grand-daughter of famous Southern statesman

John C. Calhoun. Floride visited the Falls in 1863, arriving

on the September 7th and spending time viewing the rapids

and gorge. She reported that the hotel "is a perfect den

of secessionists, most driven from New Orleans by

(Northern General Benjamin) Butler. The rest are English."

No doubt some Floride met were Confederate agents

and their many contacts.

Floride wrote her mother on September 12th that after

leaving Niagara:

"the next station to the Suspension bridge having burnt

down the night before, doing some damage to the track,

we had to go to a place called Tonawanda where we

waited a weary while, then struck back into the NY

Central railroad at Lockport."

Future famed Confederate General Thomas J. Jackson

and wife honeymooned in Niagara Falls in the late 1850s

and perhaps stayed at the Clifton House.

The building burned on June 26, 1898, rebuilt in 1906,

then ravaged by fire once again in 1933.

Privateers, Secret Agents and Liberating Southern Prisoners:

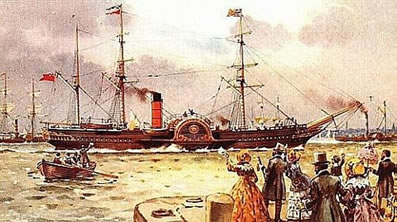

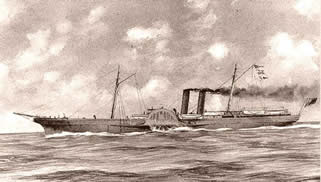

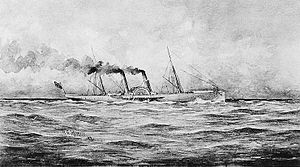

The Confederate privateer Tallahassee left Wilmington on

August 7, 1864, slipping past the blockaders for a devastating

raid on Northern merchant shipping.

Heading northward, the Tallahassee’s Captain John Taylor

Wood contemplated a raid into the port of New York after

capturing the Sarah A. Boyce near Sandy Hook.

“Panic swept the North” as no Northern warships were

available to defend the harbor. Deciding against the raid,

Wood took the Tallahassee up the northern coast, capturing

and destroying any enemy merchantmen that crossed his path.

On August 18th, the Tallahassee made port at Halifax for

coal and repairs, then proceeded southward, entering

Wilmington on the night of August 25th -- her toll

on Northern shipping for that voyage was 33

merchantmen, of which 26 were burned,

two were released and five bonded.

The Tallahassee would later become a blockade runner

and renamed the Chameleon, captained

by John Wilkinson.

|

Captain John Wilkinson |

An early plan to have the Northern homefront feel the

effects of war occurred in mid-1863. Southern commandos

led by Robert D. Minor and endorsed by Secretary of the

Navy Stephen Mallory, were planning to capture

Northern ships on the Great Lakes and turn their

guns on Toledo, Cleveland and Buffalo in retaliation

for the destruction and burning of Southern cities.

Minor and his 15 Confederate Marines departed

Wilmington on the blockade runner Robert E. Lee

under the command of veteran Captain John

Wilkinson on October 7, 1863. They arrived in

Halifax on the 16th where Wilkinson turned the

Robert E. Lee over to another captain, but quickly

found that the plan had been discovered and

announced in Northern newspapers. The plan

was abandoned and the party returned South.

At the urging of President Davis, the Confederate Congress

passed a Secret Service Act in 1864 to provide $1 million for

“clandestine operations,” most of it planned for use in Canada.

Davis dispatched commissioners, agents and funds to Canada

for an effort to aid Southern prisoners in their escape from

Northern prisons, and take advantage of the political unrest

and Midwesterners (and New York) opposition to the war.

In April 1864, Davis sent Clement C. Clay of Alabama,

James Holcomb of Virginia, Captain William Cleary of Kentucky

and Jacob Thompson of Mississippi to Canada for this purpose,

leaving Richmond on May 3rd for Wilmington, and departing

on the blockade runner Thistle for Canada on May 6th. These

were very distinguished Americans aboard the Thistle,

Thompson being President Buchanan’s Secretary of the

Interior, and Clay serving two terms as a United States

Senator from Alabama in the late 1860’s. The runner Thistle

was escorted by the ironclad CSS Raleigh, which turned

south to engage blockading ships whilst the Thistle ran

north for a spell, then eastward to Bermuda. It was

only through the extraordinary efforts of Captain John

Pembroke Jones, commanding the Raleigh, in keeping

the blockaders distracted that the mission was not

captured off Wilmington.

Captain John Pembroke Jones

Once in Canada, the commissioners went to work, with

Holcombe in particular establishing “a network of agents

in Montreal, Toronto, and Windsor (across from Detroit),” to channel escaped Southerners toward Halifax, and thence to Wilmington.

This excerpt from a letter to the Secretary of State from

Commissioner Holcombe reveals his plan::

Clifton House, Niagara Falls, Canada West, August 11, 1864

To: Honorable Judah P. Benjamin, Secretary of State, CSA:

Sir---Since my last dispatch I have visited all the points in

Canada at which it was probable any escaped (Southern)

prisoners could be found. I have circulated as widely as

possible the information that all who desired to return to

the discharge of their duty could obtain transportation

to their respective commands within the Confederacy.

For this purpose I have made arrangements with reliable

gentlemen at Windsor, Niagara, Toronto and Montreal

to forward such, as from time to time may require this

assistance, as far as Halifax, from which point they will

be sent to Messrs. Weir & Company to Bermuda. The system

thus organized will provide for the return of any ordinary

average of escaped prisoners.

With the highest respect, etc.,

James P. Holcombe

Clement Clay posted himself at St. Catherines, a small town

not far from Niagara Falls on Lake Ontario. From here he

conducted his efforts to effect negotiations for peace and

“making overtures…to important men in the North.”

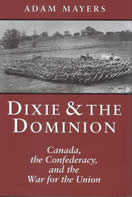

As Adam Mayers states in his “Dixie and the Dominion,”

“there were at least three parallel operations being run

in Canada,…Thompson focused on an uprising in the

Northwest (and) Holcombe and Clay wanted to return

escaped prisoners to the South and mount an anti-war

campaign by influential men in the North.”

The Lake Erie Raid:

In 1864, the agents in Canada were planning the escape of

Southern soldiers imprisoned at Johnson’s Island on Lake

Erie near Sandusky, Ohio. The plan was to overpower the

crew of the USS Michigan, the lone US warship on the Great

Lakes which guarded the prison and release the nearly

3000 prisoners to create a small, but formidable army

deep in enemy territory.

Among the Confederate agents in Canada was Lt. Bennett Young

of Kentucky, who would later lead the attack on St. Albans,

Vermont and burn several buildings on October 19, 1864.

Young was a cavalryman with John Hunt Morgan, captured

in July 1863 and imprisoned at Camp Douglas near Chicago.

Young escaped from prison and made his way back to the

Confederacy via the St. Lawrence River to Halifax, then to

Bermuda, and then to Wilmington aboard a blockade runner.

Bennett Young

Confederate Secretary of War James Seddon had sanctioned

Young’s plan of action in Canada, and ordered him return to

Canada and scout the towns along the American border,

feeling free to sack and burn those most exposed. Seddon

continued, “It is but right that the people of New England

and Vermont especially, some of whose officers and troops

have been foremost in these excesses (in the South), should

have brought home to them some of the horrors of such warfare.”

Jacob Thompson and his agents were busy rounding up escaped Confederate prisoners in the North and found the Niagara region a convenient headquarters. The old Suspension Bridge at Niagara Falls

was a well-traveled entry into New York for reconnaissance missions,

and agents were aided by Southern-sympathizers in Fredonia,

and Dunkirk, New York. Agents met in the Genesee Hotel in

Buffalo to plan the John’s Island operation and also used nearby

Port Colborne in Ontario as a staging area.

It is important to note that New York had those sympathetic

to the Southern cause of independence who might assist the

Confederates. As an example of this, on April of 1861

Democratic leader and New York Assemblyman

Francis Kernan stated that:

"I am opposed to, and I trust the National Government will

not attempt to carry an aggressive war into the Southern States.

Such a war will neither preserve or restore the Union . . .

If, we cannot adjust our differences now by concessions

which will make us one people, is it not better

to separate peaceably?"

Unfortunately for the South, the Johnson’s Island liberation

plans went awry with the Confederate agents betrayed by one

of their small group, Northern authorities were alerted,

and additional Northern troops were sent to the prison as

a precaution. A further difficulty facing the Confederate

agents was Lincoln’s infiltration of Democratic political

groups who longed for peace. An immediate result of

the failed Fort Erie Raid and the ease with which the

agents had used the Niagara region as a base, was a

regiment of Northern troops being sent to Buffalo

to effectively patrol the border.

On his return to the South from Halifax in late September 1864, Confederate Commissioner Holcomb ran the blockade into

Wilmington aboard the Condor which went aground on the

burning hulk of the runner Night Hawk from Bermuda,

destroyed earlier that night at the entrance to New Inlet Bar.

While Holcomb made it ashore, his companion and famed

Confederate spy Rose O’Neal Greenhow was lost when the

lifeboat capsized. She was carrying $2,000 in gold and sank

with her money recently acquired from the sale of her book,

“My Imprisonment and the First Year of Abolition Rule

at Washington,” published in England. Once safely ashore,

Holcomb continued his journey to Richmond to report to

President Davis on the South’s espionage efforts in Canada.

Peace Conference at Niagara Falls:

While the escape attempt at Johnson Island was planned, others

sought peace between North and South. President Jefferson

Davis authorized George N. Sanders of Kentucky and

commissioner Clement Clay to conduct a peace conference

with Northern authorities in July 1864, with Lincoln sending

his Chief of Staff, John Hay in his behalf. New York Tribune

editor Horace Greeley endorsed the peace talks and wrote

Lincoln “our bleeding, bankrupt, almost dying country longs

for peace, shudders at the prospect of fresh conscription,

of future wholesale devastation and new rivers of blood.”

The negotiations took place at the famous Clifton House Hotel

and came to naught as Hay pressed Lincoln’s demand for

no political independence of the South, and the abandonment

of slavery by federal edict. Davis would accept no terms

other than full political independence.

Thompson’s Desperate Last Plan:

With the failures of Confederate attacks at Camp Douglas and

Johnson’s Island, Commissioner Jacob Thompson sensed the

tightening of Canadian security measures against Confederate

agents as the US government pressured Canada. But Thompson

had one more plan to put forward in the last days of the

Confederacy -- and it involved Lee’s army breaking out of

its defensive position at Richmond and Petersburg,

and moving north.

Lee would threaten Washington first, move westward to

capture Pittsburgh and Wheeling to establish a base, then

send units to free the 100,000 prisoners held in various

Northern prisons. Lt. John Headley, one of the agents

in Canada, wrote after the war that the plan seems bizarre in

hindsight, but at the time it had valid appeal.

He wrote that “the South was exhausted…and that

nothing could be lost and everything could be gained.”

He surmised that though the South would be at the mercy

of the enemy, the Northern people and property would be

equally in the power of the Confederates, who would

be unopposed marching westward. With the South’s armies

collapsing and Lee against any plan that would perpetuate

the slaughter, the plan came to naught.

The War Ends For Captain Maffitt:

In mid-January 1865, legendary Wilmington blockade runner

Captain John Newland Maffitt was in command of the Owl,

and had just slipped into the Cape Fear River when local

patriots informed him of the fall of Fort Fisher.

A swarm of Northern blockaders then descended upon the

Owl with “ inexperienced enemy seamen firing wildly and in

all directions,” and according to Maffitt, “this was attended

with unfortunate results to the Federals.” Maffitt then sailed

to Nassau for repairs, and ran the blockade into Galveston,

Texas in early May. In search of Maffitt was Lt. John

Pembroke Jones who had sufficient Confederate funds

to purchase two steamers to ferry supplies to the

beleaguered Lee in Virginia. But after learning of Lee’s

capitulation in April, Maffitt set sail for Halifax to coal,

and leaving Lt. Jones there, went on to exile in

Liverpool, arriving on July 14, 1865.

Southern Exiles at Niagara on the Lake:

After Lee’s surrender in Virginia and Gen. Joseph E. Johnston’s

capitulation in North Carolina, many high Confederate officials

were arrested by the Radical Republicans and some fled the

country to watch the postwar period unfold from afar.

Many went to Mexico and Brazil to become “Confederados,” some

like Judah P. Benjamin (who spent some childhood years in

Wilmington) went to England, and some to Canada. The latter were

found in Montreal, Toronto, and later Niagara on the Lake which

was situated at the mouth of the Niagara River, and directly across

from Fort Niagara.

The small town, originally named Newark, saw much activity during

the War of 1812 when nearby Fort George was captured by

American forces under General George McClure. On 10 December

1813, McClure’s men set fire to the town before abandoning

the fort to advancing British forces, destroying eighty homes

and “about 400 women and children were rendered homeless.”

As Newark had been the early capital of Upper Canada and to

every loyal Canadian it symbolized the early struggles of the

province and the names of Simcoe and Brock---its destruction

(and the burning of York’s (Toronto) public buildings earlier)

infuriated the British and led to the retaliation burning of

Washington, DC in August 1814.

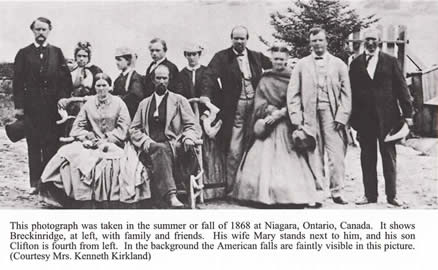

The war’s end brought General John C. Breckenridge and his

family to Toronto first, and then Niagara on the Lake in May 1866.

Breckenridge served as vice president of the United States under

James Buchanan 1856-1860, was a candidate for president in 1860

on the Southern Democratic ticket, (received nearly 850,000 votes)

and a Major General in the Confederate service.

He and his family rented a small home on Front Street overlooking

Lake Ontario for twelve dollars a month. Immediately opposite the

home on the New York bank of the river was Fort Niagara.

Breckenridge gazed at the fort often, “with its flag flying to refresh

our patriotism.” To him it seemed both a symbol of the Founder’s

republic he tried to save, as well as a taunt that threatened arrest

should he cross the river.

One who frequently visited the exiled Southerners was Lt. Colonel

George T. Denison, commander of the Canadian Governor-General’s Body Guard, another was General Breckenridge’s “beloved old

adjutant,” J. Stoddard Johnston of New Orleans. Johnston was the

nephew of General Albert Sidney Johnston, and also served as

an aid to Generals Bragg and Buckner.

General George Pickett was also in Canada, though perhaps

living in Toronto. Soon to join the ex-vice president at Niagara on

the Lake were Confederate commissioner to England James M.

Mason, General’s Jubal Early, John McCausland, Richard Taylor

(son of General Zachary Taylor), John Bell Hood, Henry Heth,

William Preston; and a host of lesser officers and their families.

They often commiserated in the shade at Mason’s home,

“discussing military matters and the practice of the

soldiers art under the modern conditions inaugurated”

by the War Between the States.

President Jefferson Davis arrived in Toronto aboard the steamer

Champion on May 30th, 1867, met by several thousand well-

wishers at the foot of Yonge Street. He boarded the Rothesay

Castle at 2PM for the journey across Lake Ontario to Niagara

on the Lake. He was met there by the Town Council along

with General Breckinridge and Mason.

Upon leaving the wharf, Davis looked across the river to

Fort Niagara with the Stars and Stripes floating over it.

He turned to his former commissioner and exclaimed:

“Look there Mason, there is the gridiron we have been fried on.”

Davis enjoyed supper at the Mason’s home on Gage Street,

and a band later came to the house and played “Dixie” for the

President. After coming to the porch to enjoy the music,

he told the small crowd that “I thank you for the honor you

have shown me. May peace and prosperity be forever

the blessing of Canada, for she has been the asylum of many

of my friends, as she is now an asylum for myself.

I hope that Canada may forever remain a part of the

British Empire and may God bless you all…”

Davis stayed in Niagara on the Lake, according to author

Nicholas Rescher, “until his 59th birthday on June 3rd, when he

returned to Montreal via Toronto and accompanied by Mason.

After he had returned to Montreal, the Niagara Mail amply

reciprocated Davis’ cordial sentiments (with) “It is a subject

of pride to Canadians that they can offer the hospitality of the

soil and the shelter of the British flag to so many worthy men

who are proscribed and banished from their homes for no

crime at all, viz. to assert the right of every people to choose

their own form of government.”

“What A Brave Fight They Have Made”

A fitting tribute to the Southerners who fought for their independence

in 1861 through 1865 came from Canadian leader John A. McDonald during the Canadian Confederation debates.

McDonald told an audience that “they could make a great nation,

capable of defending itself, and he reminded them of “the gallant

defense that is being made by the Southern Republic---at this moment

they have not much more than four millions of men---not much

exceeding our own numbers---

yet what a brave fight they have made.”

Bibliography:

Rogues and Runners, C.L. Deichmann, Bermuda National Trust, 2003

Guns For Cotton, Thomas Boaz, Burd Street Press, 1996

Dixie and the Dominion, Adam Mayers, Dundurn Group, 2003

Gray Phantoms of the Cape Fear, Dawson Carr, Blair Publisher, 1998

Breckenridge: Statesman, Soldier, Symbol, W. C. Davis, LSU Press, 1974

Running the Blockade, Confederate Veteran Magazine, 9/ 1916

CSNavy Research Guide, Thomas T. Moebs, Moebs Publishing, 1991

Niagara on the Lake-Confederate Refuge, N. Rescher, NAP 2003 Secession Movement, Middle Atlantic States, W.C. Wright, AUP, 1973 A Rebel Came Home, McGee/Landers editor, USC Press, 1961

©2006 Cape Fear Historical Institute