Mission Statement:

"To advance through research, education and symposia, an increased public awareness of the Cape Fear region's unique history."

Benjamin Franklin Grady

Educator, Patriot, Statesman

Cape Fear Historical Institute Papers

United States Congressman Benjamin Franklin Grady

One of the most distinguished sons of North Carolina

is Benjamin Franklin Grady (pronounced “Graddy”),

an accomplished author and one who served his region

as an educator, Justice of the Peace, Superintendent

of Public Instruction, and United States Congressman

from 1891-1895.

Grady was born on October 10, 1831 near Serecta in the

Albertson Township, the descendant of a great-great-grandfather

who emigrated from Ireland in 1739. He was the oldest son of

Alexander Outlaw and Anne Sloan Grady.

The Grady and O’Grady’s genealogy is traced back to Ireland

in the 4th Century, and in 1365 a John O’Grady is found as

Arch Deacon of Cashell; in 1405 another John O’Grady

was Bishop of Elfin---the cathedral founded by St. Patrick

in the mid-5th Century. A Standish O’Grady was appointed

Attorney General of Ireland in May, 1803 and later served

as a Justice and Chief Baron of the Exchequer.

The first Grady to settle in Duplin County was John, who acquired

fertile land at the fork of the Northeast River and Burncoat Creek

in 1739. He was to marry Mary Whitfield. Two sons of this

union, John and Alexander, were to fight at the Battle of

Moore’s Creek Bridge in 1776; the former losing his life

there and for whom the lone monument memorializes.

After the Revolution, Alexander Outlaw Grady and wife

Nancy Thomas lived on the family farm, and his son Henry,

referred to by the Grady family as “Lord Harry,” married

Elizabeth Outlaw on January 6, 1799. This last marriage

produced Alexander Outlaw Grady on February 17, 1800.

Alexander would marry Anne Sloan, daughter of Gibson and

Rachel (Bryan) Sloan in 1830, and the following year would

witness the birth of Benjamin Franklin Grady.

Grady's Early Years:

Alexander Outlaw Grady was a slaveowner with “twenty-five

or thirty slaves” who were Grady’s playmates and friends

during his childhood, and Grady related that “as I grew up

I hunted and fished with the Negro boys, and worked with

them in the fields and woods except during about three months

each winter when I attended the “old field schools.” He states

that “My boyhood days were spent on the farm, where I

worked with the slaves during nine months of the year…”

As was common in antebellum North Carolina, his father

and neighbors employed a classical scholar to teach their

children ten months in each year from which Grady. benefited,

and in 1851 he was under the instruction of Rev. James M.

Sprunt who taught in the Grove Academy in Kenansville.

Grady entered the University of North Carolina in September

1853 and graduated four years later, returning to Kenansville

to teach two years at the Grove Academy under Dr. Sprunt’s

supervision. He obtained the position of professor of mathematics

and natural sciences at Austin College, located at Huntsville,

Texas, beginning work there in the summer of 1859.

Grady continued in his position until classes were

suspended by impending invasion in 1861, and in his words,

“soon afterwards typhoid fever prostrated me and

unfitted me for military service until May 1862.” Grady

married Olivia Hamilton (a grandniece of Alexander Hamilton)

of Huntsville, Texas and they had one son named Franklin.

Olivia passed away in 1863 whilst Grady was a prisoner of

war, and he later married Mary Charlotte Bizzell of Clinton,

North Carolina in 1870. This marriage produced nine children.

In his own brief biography in 1898, Grady writes of

his father’s prevalent political beliefs:

“By intermarriages his (my great-great-grandfather’s)

blood in my veins was intermingled with that of

the Whitfield’s, Bryans, Outlaws and Sloans. All these

families were Whigs during the Revolutionary War;

and they were advocates of “strong government”

in 1788-1789. Most of them, however, if not at all,

gradually drifted toward Jefferson’s exposition of the

powers of the Federal Government; and my father,

Alexander Outlaw Grady, became a disciple of

John C. Calhoun in 1832-1833, after hearing that

statesman defend his position before the

General Assembly of North Carolina, of which

my father was a member.

In 1860-1861, he was a secessionist.”

Military Service:

Grady enlisted in a local unit which eventually became K

(troop) of the 25th Texas Cavalry Regiment under General

(Thomas C.) Hindman, but was soon dismounted leaving

him to serve as infantry. He served as an Orderly Sergeant

during the war and twice refused the captaincy of a

company in order to carry a rifle, often

detailed as a sharpshooter.

Grady reported of his capture by Northern forces:

“On January 11, 1863 we were captured at Arkansas

Post---about 3000 of us and 45,000 of the enemy

with 13 gunboats--- and carried to Camp Butler

near Springfield, Illinois.”

Grady wrote of the inhuman treatment at the hands

of his Northern captors, writing that Southern prisoners

were shot at by guards for refusing to remove their caps

in the presence of Northern officers, robbed of any

personal effects and exposure to the cold winters with

only a blanket as protection.

In the middle of April 1863 Grady was freed in an

exchange for Northern prisoners held by Southern forces,

and sent to General Braxton Bragg’s command near

Tullahoma, Tennessee. He fought with Bragg’s army

as it moved to North Carolina near the end of the war,

serving in (General Hiram B.) Granbury’s Brigade of

(General Patrick R.) Cleburne’s Division in

(General William) Hardee’s Corps. Grady was lucky

to survive the war in Cleburne’s division as every

officer above lieutenant rank had been killed by the

end of the war, including Cleburne and Granbury.

He participated in all the engagements of his brigade

(excepting Nashville and Bentonville): Chickamauga,

Missionary Ridge, New Hope Church, and Atlanta;

and witnessed the deaths of his commanders Granbury

and Cleburne at the Battle of Franklin

in November of 1864.

Grady writes: “On the 19th of March 1865, while

he cannon were booming at Bentonville, and my

command preparing to leave the railroad for the

scene of action, I was sent by our surgeons to Peace

Institute Hospital in Raleigh where typhoid

fever kept me till May 2.”

Grady lost two brothers in the war, one killed at

Bristoe Station and the other at Snicker’s Gap; his

remaining brother would lose a hand. He was

himself wounded twice, suffering a hand wound

and one to the face that left a deep scar

near the right eye.

Grady describes his view of the South’s war for

independence in the following passage from his

“Case of the South Against the North”:

“I did not agree with my father regarding the

policy of nullification or of secession. While I

subscribed to the doctrine that no State in the

Union had ever relinquished the right to be its

own judge of the mode of measure or redress

whenever its welfare and it peace should be

put in jeopardy by the other States, acting

separately or jointly, I doubted whether the

nullification of a Federal act was consistent

with the obligations imposed by the “firm l

eague of friendship” with the

unoffending States, if any….”

“As to secession, I believed it to be the best

for the Southern States to remain in the Union,

and trust to time and the good sense of the

intelligent people of the Northern States

for justice to themselves and their children.

This hope was strengthened by the

circumstance that the interests of the

expanding West being identical with those

of the South, the time was not far

distant when that section would join the South

in the struggle for riddance of the burdens

imposed by the shipping, fishing, commercial

and manufacturing States of the East.”

Grady concludes by stating:

“this was the stand I took and held until

Mr. Lincoln compelled me to choose whether

I would help him to trample on the

Constitution and crush South Carolina,

or help South Carolina defend the principles

of the Constitution and her own “sovereignty,

freedom and independence.” I went with

South Carolina as my forefathers went with

Massachusetts when “our Royal Sovereign”

threatened to crush her.”

Postwar Life and Teaching:

“without money, without decent clothing, and

suffering from the effects of the fever, I went to

my father’s (home) and obtaining employment in

the neighborhood at my chosen profession,

I waited on him in his last sickness and saw him

die of a broken heart in the year 1867, having

survived the war and lived to see the dark

shadow of “reconstruction” and government

by the ex-slaves hovering over

his beloved Southland.”

Thus Grady returned to his hometown of “Chocolate”

at war’s end. His father dead of a broken heart,

the family servants had scattered,

and the farm was in ruinous condition.

He returned to education and after organizing a school

in Moseley Hall (today LaGrange) and teaching for two

years, he established the Clinton Male Academy with

fellow teacher Murdock McLeod at nearby Clinton

(Sampson County). There Grady taught until failing

health in 1878 forced him to return to his Duplin

County family homestead to farm where he, his

father, grandfather, and great-grandfather were born.

Grady continued to teach at his home, and provided

instruction for young men unable to attend the university;

and additionally conducting Sunday school at Sutton’s

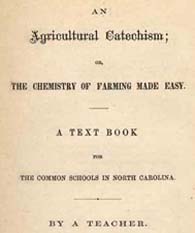

Branch School House. In 1867 he published a school

textbook entitled “An Agricultural Catechism,”

and would go on to write two more books at the

end of the century.

Public Service:

The mid-1870’s would see Grady begin a long career

of public-service beginning with Justice of the Peace

(1878-1889); appointed a Trustee of the re-established

University of North Carolina in 1874 (serving until

1891 when congressional duties limited his time);

and elected Superintendent of Public Instruction for

Duplin County in 1881, serving in that capacity for eight

years. While serving as Superintendent, brother Stephen

Miller Grady held the post of Chairman of the

Board of Education as both advanced the cause

of education in Duplin County.

Grady was elected twice as a United States Representative

to Congress from the Third District (Democrat), serving in

Washington City from March 1891 to March 1895 in the

52nd and 53rd Congresses. He was known by his

congressional colleagues as “the encyclopedia as

his mind remembered everything. He campaigned for

repeal of the Sherman Act of 1890, writing the

New York Times on June 11, 1893 from

Wallace, North Carolina:

“I prefer a cheap money of our own. I will vote to

repeal the Sherman law with a free coinage

substitute and a tax on State banks. Let the

people rather than the Government

control money volume.”

Benjamin Franklin Grady held political views consistent

with his North Carolina roots, especially regarding the

War Between the States. In May 1894 while serving

as a US Representative he penned a response to a

Pennsylvanian in which he reflected upon the dismal

outcome of that war. He condemned the

“cranks, fanatics and unscrupulous tyrants” who

were in national political power and regarded

his own State of North Carolina as a conquered

province of the victorious North. He saw the

unbridled military power of the Washington

government unleashed during the War as dangerous;

and verbally attacked the “advocates of imperialism”

who viewed the globe as their own.

His viewpoint on the War Between the States as this:

“the cause of the South was the cause of Constitutional

government, the cause of government regulated by law,

and the cause of honesty and fidelity in public servants.

No nobler cause did ever man fight for!”

Grady was wary of politicians and government,

and saw that “Extravagance is almost unavoidable when

the method of taxation enables the Legislature to lay

unperceived burdens on the shoulders of the taxpayers.”

He saw too the dangers of unrestrained democracy

and demogogues as:

“written constitutions present no effective barrier to

the avarice of classes, the ambition of individuals,

the schemes of party, or the machination of fanatics;

and so long as the mass of the people are unable

to understand the structure and administration of

their Government, they will continue to be dupes of

callow statesmen and professional office-seekers,

and victims of misgovernment."

He looked to future generations of Americans to recognize

misgovernment and to strive for the vision of the Founders

by stating:

“We cannot retrace our steps or right the wrongs

of the past; but it is not too much to hope that a

more enlightened generation now entering

upon the duties of guarding themselves and

their posterity from recurrences of the mistakes

of the past, may strive to restore and vivify the

principles on which alone any just government

can be founded, and by reestablishing the system

of governments in and between these States

which our fathers hoped would be “indestructible,

“insure domestic tranquility” and “secure the

blessings of liberty” to themselves and their posterity.”

Return to Teaching:

In 1899 Grady established the Turkey Academy

(in Turkey, NC) with son Henry Alexander who had

studied law at the University of North Carolina. Since

1896 Henry had been working as a law clerk with his

half-brother Franklin, an attorney in New York City,

who had earned a law degree at Georgetown University.

In 1900, Henry would leave the Academy in the summer

of 1900 to pursue a short law course at the University of

North Carolina, and being licensed to practice by the

Supreme Court in September 1900. For three years he

was a member of the firm Faison & Grady of Clinton,

his partner being the well-known Henry Faison.

He afterward became a partner of Archie McLean Graham,

a connection that was maintained for twenty years. In 1922

he was elected to the bench of the County Court in Sampson

County and continued to serve in that capacity until

January 1, 1939, when he retired and under law became

emergency judge of the Superior Court for life.

After Henry Alexander’s departure, Grady would spend

his last years “teaching and pursuing literary work.” His literary

retirement gave him time to write two exceptional books, the

first published in 1899 entitled “The Case of the South

Against the North; and the second published in 1906,

“The South’s Burden.” Both are articulate and well-reasoned

Constitutional arguments regarding the Southern States

struggle for independence from 1861-1865. They are

currently reprinted and available

through www.confederatereprint.com.

Benjamin Franklin Grady died on the 6th of March, 1914

and is buried in the Clinton Cemetery.

Grady’s son Henry Alexander went on to legal success

as mentioned above, and the other siblings were Cleburne;

James B.; Stephen S.; Benjamin; Louis D.; Lessie R.;

Mary Eva; and Anna B. Grady.

It is said that Benjamin Franklin Grady was a

lover of literature and:

“as scholarly a man as ever lived (and a) first class

man in Greek, Latin, French, and mathematics at

the university, a born teacher, (and) conveyed

to his son(s) his knowledge in such a way the son’s

education is equal to that of any college graduate.”

After his death, the Sillers Chapter of the United Daughters

of the Confederacy in Clinton wrote the following about

Grady in their periodical, the Southern Cross:

“Franklin, as he was called by the family, attended the

old field schools and was prepared for College by the

Rev. James Sprunt. Among his classmates were

Colonel Thomas S. Kenan, Judge A.C. Avery,

Major Robert Bingham, Dr. D. McL. Graham,

Captain John Dugger, Honorable John Graham,

and many others of like kind, who have helped to

make history honorable in North Carolina.

Two of his brothers had been killed in the war, one

at Bristoe Station and one at Snicker’s Gap; while

the remaining brother had lost the use of a hand.

He saw that it was necessary to build up a New South

upon the ruins of the past.

Teaching was his chosen profession and he believed

that in the education of the people lay the

salvation of the country.”

Sources:

Dictionary of North Carolina Biography, William S. Powell, 1986

Henry Alexander Grady, Biographies of Leading Men, L. Wilson, 1916

Case of the South Against the North, B.F. Grady, 1899

The South’s Burden, The Curse of Sectionalism, B.F. Grady, 1906

North Carolina: Old North State and the New, A. Henderson, 1941

©2006 Cape Fear Historical Institute