Mission Statement:

"To advance through research, education and symposia, an increased public awareness of the Cape Fear region's unique history."

Ironclad Defender of the Cape Fear

CSS Raleigh

Cape Fear Historical Institute Papers

Ironclad CSS Raleigh, Defender of the Cape Fear:

Its keel laid down in the Spring of 1862 at James Cassidey’s

shipyard in Wilmington and construction delayed by the

shortage of materials, the CSS Raleigh was commissioned

by the Confederate States Navy on 3 April 1864 and under

the command of Lt. John Wilkinson. (an early image of

Wilkinson appears below)

This officer had returned from Canada where he led "a

party of twenty-six officers of the different grades" to free

Southern prisoners at Sandsky, Ohio and capture the USS

Michigan on Lake Erie -- a brilliant operation had the secret

operation not been compromised.

Wilkinson's assignment to the CSS Raleigh

lasted only a few weeks as he was ordered to Richmond

to be part of an operation to free Southern prisoners

at Point Lookout.

Command of the CSS Raleigh fell to Lt. John Pembroke

Jones, an officer very familiar with local waters as he was

part of the US Navy’s Coast and Geodetic Survey

detachment in the 1850s which surveyed and charted

the coastline in this area.

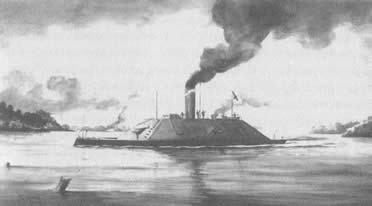

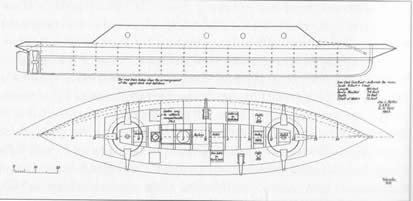

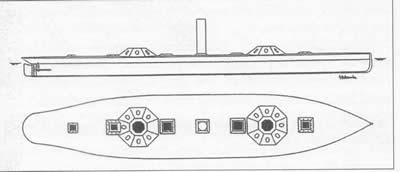

The CSS Raleigh was a Richmond Class ironclad, designed

by Capt. John L. Porter, Chief Naval Constructor for

the Confederate States Navy. Its length was 150 feet

(172’ overall), a beam of 32 feet, drew 12 feet of water,

and armament consisted of 4-6” guns and perhaps a spar

torpedo. To man the vessel, 197 officers and crew, plus

a detachment of 24 marines were aboard.

The steam engine of the wrecked blockade runner

Modern Greece blockade was briefly contemplated to

power the Raleigh, but to no avail. No plate indicating

engine origin exists, and one from the Schockoe Foundry

in Richmond may have powered this ironclad.

For the dual purpose of stealth and surprise, an eyewitness

account observed the hull, casemate, pilot house and

smokestack of the CSS Raleigh were all dark blue; gun

muzzles were painted black or simply left as unfinished iron.

This is from an eyewitness account.

Why the Ironclads:

Unable to match the US Navy in shipbuilding and high-seas

warships, Confederate naval strategy developed three main

categories: coastal/harbor defense; blockade breaking and

running; and river defense. The revolutionary ironclads could

devastate the wooden Northern ships which formed most of

the blockading squadrons, and ships like the Raleigh could

(and would) scatter blockaders fearful of

being rammed and sunk.

Ironically, this strategy of Secretary of the Navy Stephen

Mallory to defend the rivers and sounds with gunboats

emulated North Carolina’s colonists during the Revolution

as they faced formidable British naval power and a blockade.

The ports of Wilmington, New Bern and Edenton were

the sites of the fledgling North Carolina naval force.

The brigs George Washington and Eclipse were built

at Wilmington in 1777, but two British warships at

Smithville (now Southport) effectively closed the port at

Wilmington, cutting off trade and sinking several ships

at anchor at Brunswick Town. Despite North Carolina’s

plans to build a navy to combat the British blockade,

the completed ships like the General Washington were

greatly outgunned, unable to leave port and later scrapped.

Nonetheless, Wilmingtonians in early January 1861 were well

aware of this closing up of the Cape Fear River by enemy

ships and were motivated to seize Forts Caswell and

Johnston to preclude it once the Star of the West armed

expedition to reinforce Fort Sumter was discovered.

The construction of the ironclads would further protect

the river and reinforce the forts; enemy ships would be

foolish to enter the Cape Fear where they would face

the guns of the CSS North Carolina and CSS Raleigh.

The First CSS Raleigh:

The first CSS Raleigh was a small, iron-hulled and prop-

driven steamer operating on the Albemarle & Chesapeake

Canal early in the war. Under the command of Lt. J.W.

Alexander, her entire service was in coastal North Carolina

and Virginia waters. The Raleigh supported Forts Hatteras

and Clark in August 1861, and defended Roanoke Island

in early February 1862. The following month she was a

tender to the CSS Virginia during its fight with a Northern

ironclad at Hampton Roads. In May 1862 she steamed

up the James River for patrol service and was renamed

“Roanoke,” then destroyed by retreating Confederate

forces on 4 April 1865.

Quickly to Battle:

With the armor installed and anxious for action against the

blockading fleet off Smithville, the CSS Raleigh saw its first

test on 6 May 1864, a little over a month after its

commissioning. Flag-Officer William F. Lynch, naval

commander at Wilmington, organized a blockade-

breaking flotilla consisting of the CSS Raleigh and the

lightly-armed steamers Yadkin and Equator, and they

steamed across the bar on that afternoon. Following

them at a distance was a blockade runner rightly

anticipating the enemy fleet being scattered.

It would be evening before the USS Britannia sighted

the flotilla, alerted other blockaders with rockets and retreated.

The CSS Raleigh fired and made at least one hit before the

Britannia pulled out of range, and this action allowed the

blockade runner to escape to sea.

About midnight the Raleigh came across the USS Nasemond

and fired upon it before it too drew out of range, the

Northern ships experiencing a nervous case of “ram fever.”

While out at sea the CSS Raleigh was spotted by the

incoming runner “Annie” which took advantage of the

enemy fleet’s scare and steamed into past Fort Fisher

with its cargo.

By dawn a reporter for the Wilmington Daily Journal was

monitoring the action from atop the fort’s 54-foot Mound

Battery. He wrote: “Daylight first disclosed the small steamers

Yadkin and Equator about two miles from shore awaiting orders

from the Raleigh…Soon the horizon was clear and we discovered

the iron-clad eight miles to sea, in quiet possession of the

blockading anchorage.”

The Raleigh first spotted the screw-steamer USS Howquah

and started a morning of futile ramming attempts and long-range

dueling – getting within a mile or so of the enemy vessel.

All told, 4 or 5 enemy ships tried to engage the Raleigh,

but to no effect except for two shots from the Howquah

bouncing off the Raleigh’s armor. The ironclad put a

round through the smokestack of the Howquah before

the Raleigh considered turned homeward to beat the tide.

By 7AM the tide was high, but to continue the engagement

the Raleigh would need to wait twelve hours for the next high

tide to cross the bar. The defenders of Fort Fisher saw the

Raleigh “steam[ing] defiantly around [the enemy’s blockading]

anchorage, eight miles from the guns of Fort Fisher, not one

dared to take up the gauntlet.”

At 7AM, the Raleigh turned its bow toward the shore, the

“little trio formed in line some five miles out, and steamed

slowly in, the Confederate flag flying saucily above

their decks.” (Peebles, p. 48)

As the Raleigh steamed across the bar at New Inlet with the

enemy ships lying back at a respectful distance, the guns of

Fort Fisher “rang out nine times in salute.”

The Federal impression, according to author Peeble’s, is that

“they seemed well enough impressed with the ironclad’s

“most formidable and dangerous” appearance, further

describing the ironclad as “fast,” a good “6 or 7 knots,”

and able to turn “very quickly.” The captain of the USS

Howquah also reported that the ironclad carried “a torpedo

on her bow,” such as the CSS Atlanta had.” Another officer

noted that “if it should come out again…he doubted the

ability “of any wooden vessel on this station to contend

successfully” against the Raleigh.

Grounding:

Shortly after crossing the bar the ironclad grounded on a

treacherous shoal or “rip,” and valiant efforts to refloat her

proved futile. She broke in two on the falling tide as the sheer

weight of its armor cladding crushed the timbers. A later court

of inquiry found that the Raleigh was the victim of shoddy

construction, though her action prior to grounding was exemplary.

Had the CSS Raleigh Survived:

It is worth considering the effect the CSS Raleigh might have

had if the treacherous rip had not caught her hull, and how her

guns could have added to Fort Fisher’s defensive firepower

during the coming invasion.

As noted by author Martin Peebles, “The ability of an ironclad

such as the Raleigh to stop the passage of more than fifty ships

[past Fort Fisher] is extremely doubtful, but the attack was not

to come through New Inlet [as]…the inlet was too shallow for

the larger Federal warships to run through. An ironclad in the

river [behind the fort] would have provided the Confederates

with a much more critical advantage.

The loss of the ironclads was more critical than [General W.H.C.]

Whiting could have foreseen, especially after the second

bombardment. In addition to the fort’s one remaining land face

weapon and the [CSS] Chickamauga’s 85-pounder, an ironclad

would have added four more heavy guns to the fort’s defense.

As demonstrated by the Raleigh’s attack of May 6-7, the

ironclad could have held its range over the peninsula

from the river’s deepest channel.”

Nevertheless, a new 226’, twin-turreted ironclad under

construction at Beery’s Shipyard on Eagles Island, the CSS

Wilmington, could not be finished in time to prevent Fort Fisher’s

reduction and the only remaining warship here was the lightly-

armed raider CSS Chickamauga. The Wilmington was burned

at its stocks on February 21, 1865, when Southern forces

evacuated the city. The ironclad was about 95 percent finished

at the time, and her Columbus Naval Works machinery was

new and ready for installation.

Author William Trotter offers this: “Had Braxton Bragg been

smart enough to hold onto the outer Cape Fear defense until

the ironclad [CSS Wilmington] was launched, Admiral Porter

and General John Schofield might never have taken Wilmington,

even after the fall of Fort Fisher.

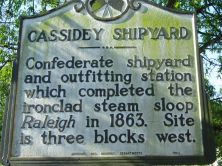

James L. Cassidey, Constructor of the CSS Raleigh:

“James L. Cassidey (1792-1866) arrived in Wilmington in the

mid-1820s and purchased two lots on the north side of Church

Street in 1828, both running from Front Street to the river.

He apparently began construction on his Federal-era house

immediately. The house may have had its gambrel roof added

in 1910, and is now known as the Cassidey-Harper House

at 1 Church Street. A later owner was Capt. James Thomas Harper.

It is not clear when Cassidey, a ship’s carpenter, actually

began the shipyard, but it appears to be by 1837. In the October

8, 1846 “Commercial,” Cassidey was advertising a “Wilmington

Marine Railway” with the ability to take vessels up to 400 tons.

After the war he merged operations with Benjamin Beery’s

facility at the foot of nearby Nun Street, with the business

renamed Cassidey & Beery. The shipyard was taken over by

Capt. S.W. Skinner in 1881; in 1911 the facility became

known as the Cape Fear Machine Works, and in 1921,

Broadfoot Iron Works.

According to author James Sprunt, “A ship full-rigged and

beautiful to look upon was built at [Cassidey’s] shipyard….to

be taken to Raleigh to the grand Whig convention rally of the party

in North Carolina on October 5 [1840]. Constitution was the

name of the ship. James [Cassidey] was on deck as her captain,

and the crew were Don MacRae, John Hedrick, John Marshall,

Eli Hall, John Walker, and Mike Cronly – then youths of fifteen

to eighteen years.

Dr. John Hill, from the residence of General James Owen….

addressed the crew of the ship and the enthusiastic throng

assemble there, and the boat then proceeded on her trip. By

rail she was taken to Goldsboro and thence by wagon, for lack

of rail, to Raleigh. The ship was left in Raleigh to be given to

the county represented in the convention which in the

presidential election should give the largest increase in the

Whig vote over the Governor’s poll, in proportion to population.

Surry County got the ship.” (Sprunt, p. 176)

The Shipyard Area:

Other shipyards in the area, John K. McIlhenny’s was circa

1833 at the foot of Queen Street. Skinner’s Shipyard was at

the foot of Church Street, circa 1911.

The Nicholas W. Schenck Diary notes: “Jas. Cassidy – occupied

half the square – high ground garden on Front Street.” End of street

was the “railway for vessels.” Today’s 1 Church Street overlooks

where the railway was located. The shipyard wharves extended

from the railway northward to Ann Street. Beyond Ann Street

were wharves for rosin, tar and lumber storage. To the left of the

railway at Church was a blacksmith and machine shop, and the

“Baptizing Dock” at water’s edge was a favorite

swimming area for boys.

John Pembroke Jones, Commander of the CSS Raleigh:

The second and last commander of the ironclad CSS Raleigh

was born 28 February 1825 at Pembroke Farm near Hampton,

Virginia, the son of John and Mary Booker Jones. He was

educated at the noted John Carey School of Hampton and

later attended William and Mary College. After one year

(in 1841) he received an appointment to the US Naval

Academy at Annapolis where he was acclaimed for his

mathematical mind. In his senior year (February, 1847)

his class was allowed to participate in the siege of Buena

Vista, thus making him a veteran of the war with Mexico.

After graduation he served in the coast surveys of North

Carolina and Virginia, and while charting the mouth of the Cape

Fear River he met and married Jane Vance London of

Wilmington. His new wife died shortly after bearing him

a son, John Pembroke Jones, Jr., born 15 December 1858.

On duty aboard the USS Congress on the African coast when

war broke out, he was furloughed home with a severe attack

of African fever. Upon reaching New Orleans, he telegraphed

his resignation and volunteered for service in the newly-formed

American Confederacy.

Jones served as an officer aboard the ironclad CSS Virginia

during its second battle with a Northern ironclad, and also

commanded the Confederate Navy ironclad, the CSS Georgia.

Probably in late March or early April, 1865, Jones was on

special service for Secretary of the Navy Stephen Mallory and

ordered to report to Captain John Newland Maffitt at Galveston,

who was to “purchase two steamers to take supplies to [General

Robert E.] Lee on an urgent basis, one for a run up the York

River and the other up the James River.”

Jones had with him money in specie checks and was accompanied

by two experienced Virginia river pilots, but found upon

reaching the Mississippi that the war in the east had ended.

Jones eventually found Maffitt who was to set sail for Liverpool,

and went as far as Halifax where Jones went ashore to

return to Virginia.

In 1864 he had married Mary Willis of Savannah who bore

him another son, Edward Jones Willis (who took his

grandfather’s name), and from Halifax he settled on Airlie

Farm, Fauquier County, Virginia. He later surveyed the

mouth of the Rio de la Plata River for the Argentine

Republic, and spent several years in Europe

recovering from ill-health.

He then made his home at Pasadena, California, where

during a visit of the United States fleet to San Francisco

he was unable to attend the fleet banquet – a vacant chair

was placed at the head of the table in his honor as the

oldest living graduate of the United States Naval Academy.

John Pembroke Jones died on 25 May, 1910 in Pasadena.

His tombstone at St. John’s Episcopal Church at Hampton

reads: “A Gallant Officer, A Cultured Gentleman, And a

Man Greatly Beloved by All Who Knew Him.”

Capt. Jones’s son, J. Pembroke Jones, Jr. received his early

education at Gen. Raleigh E. Colston’s accalimed Cape Fear

Academy in Wilmington. He married Sadie Wharton Green

of Fayetteville in October 1884, and was president of the

Cape Fear Rice Milling Company of Wilmington. They owned

the Gov. Dudley Mansion as well as what is now Airlie Gardens,

and built the lavish Italianate-styled “Bungalow” in Pembroke

Park, in what is now Landfall.

Sources:

The Confederate Ironclads, Maurice Melton, SB Books, 1968

CSN Research Guide, T.T. Moebs, Moebs Publishing, 1991

Narrative of a Blockade Runner, John Wilkinson, 1876

Land of the Golden River, Vol. 2 & 3, Lewis Philip Hall, 1980

History of a Civil War Ironclad , M. Peebles, Thesis March 1996

Chronicles of the Cape Fear, James Sprunt, Edwards & Broughton, 1916

Wilmington, NC, Architectural and Historical Portrait, Tony Wrenn, 1984

High Seas Confederate, Royce Shingleton, USC Press, 1994

Confederate Veteran, November 1910

©2006 Cape Fear Historical Institute