Mission Statement:

"To advance through research, education and symposia, an increased public awareness of the Cape Fear region's unique history."

Wilmington On The Eve of Secession: 1861

Cape Fear Historical Institute Papers

www.cfhi.net

Stephen Douglas' Prediction:

“Stephen Douglas of Illinois let everyone in hearing distance know

his prediction of the future. He said on August 21, 1858 that

“I believe that this new doctrine preached by Mr. Lincoln and this Abolition party would dissolve the union. They try to array all the northern States in one body against the South, inviting a sectional war…to last until one or the other is driven to the wall.”

(Lincoln-Douglas Debates, Holzer)

Fort Sumter Prior to Bombardment

Background: South Carolina and Fort Sumter Crisis

Upon the secession of South Carolina on December 20th, 1860, a

one-hundred gun salute was fired in Wilmington as the streets became crowded with anxious citizens. Although conservative North Carolinians denounced their neighbor’s precipitous action, Tarheels were united in opposing any use of force to coerce South Carolina back into the

voluntary union. One conservative citizen summed up the prevailing sentiment in the American South by stating,

“I am a Union man, but when they send men South it will change

my notions. I can do nothing against my own people."

Many miles to the North, a one-hundred gun salute to the

South Carolinians was also fired in Wilmington, Delaware, an

agricultural State with many trade ties to the American South.

The pro-secession Wilmington Journal of 21 February opined that the seceding States would not accept the Crittenden compromise, stating

that “it is too late in the day to talk about compromises…The border Southern States must decide to which Confederacy they will attach themselves…There can be no half-way course now.”

President James Buchanan

The Cape Fear Forts:

The “Star of the West” relief expedition sent by President Buchanan in defiance of South Carolina reasserting its independence, greatly alarmed patriots in the Cape Fear. The ship entered Charleston Harbor on

January 9, 1861 and was fired upon by Citadel cadets manning batteries

on Morris Island, driving the ship back to New York harbor.

A meeting of prominent citizens in Wilmington met at the Courthouse

after the Star of the West incident with merchant Robert G. Rankin, Jr.

as the speaker. This group formed a Wilmington Committee of Safety patterned on the one formed to resist British invasion 86 years earlier,

and they called for volunteers to join a defensive force called the

“Cape Fear Minutemen” commanded by Captain John J. Hedrick.

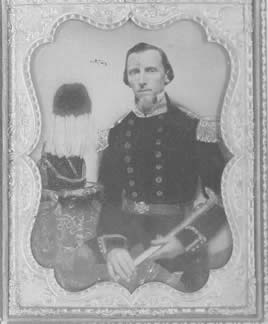

Captain (later Colonel) John J. Hedrick

Their primary concern was the two fortifications guarding the

Cape Fear, Forts Johnston and Caswell. Named for Royal Governor Gabriel Johnston, the former was ceded by North Carolina to the federal government in 1794 on the condition that a fort was to be erected

there within three years. This never occurred and only a barracks

was to exist there. The latter fort was named for Richard Caswell,

North Carolina’s first governor under

the United States Constitution.

Captain Hedrick and his small force departed from the Market Street

dock early on January 10th on a schooner bound for Smithville,

where they arrived at 3PM. They marched to the US military

barracks at Fort Johnston then in the charge of Ordnance

Sergeant James Reilly, and took charge of the supplies.

Fort Caswell on Oak Island near Smithville (now Southport)

was a bastioned, masonry fortress commanding the main entry

into the Cape Fear River, and it only mounted two 24-pounder

cannon. Though poorly-armed at the time, the fort under a

strong Northern garrison and guns would control maritime traffic

in and out of Wilmington---it had to be taken. With twenty men

from the Minutemen and Captain S.D. Thurston’s “Smithville

Guards,” Captain Hedrick sailed to Fort Caswell about three

miles distant and took charge of the fort from the

sergeant posted there, Frederick Dardenkiller.

This seizure of federal forts and stores was a preemptive strike on the

part of the Cape Fear Minutemen and Hedrick was not under the orders

of Governor John Ellis who was the commander of all North Carolina Militia. Hearing of the seizure of Forts Johnston and Caswell, he ordered Colonel John Lucas Cantwell of Wilmington and his 30th North Carolina Militia to proceed to Smithville to restore the forts to federal control.

Governor John Ellis

Ellis wrote that although Hedrick and his men were “actuated by patriotic motives,” that “in view of the relations existing between

the General Government and the State of North Carolina, there is

no authority of law, under existing circumstances, for the

occupation of the United States forts situated in this State.”

Upon his arrival at Smithville after dark on January 12th, Cantwell sent Hedrick the Governor’s orders to restore the forts to federal control. Hedrick responded in writing the next morning:

“Sir, Your communication, with the copy of the order of

Governor Ellis demanding the surrender of this post, has

been received. In reply, I have to inform you that we, as

North Carolinians, will obey his command. This post will be

evacuated tomorrow at 9 o’clock a.m.

John J. Hedrick.”

Ordnance Sergeant Walker, formerly in charge of Fort Caswell,

was restored to his post.

This re-occupation of the two forts would remain the status quo

until April, though military units were steadily recruiting and

arming to resist an expected invasion of Wilmington and the

Cape Fear. The “Minutemen” of Captain Hedrick was

reorganized as the “Cape Fear Artillery,” a name they

served under for the rest of the war.

The Wilmington Daily Journal of January 16 reports on a citizen

meeting and resolution, and what concerns motivated Wilmingtonians

to take action. “At a meeting held in the Court house this evening,

B.W. Beery in the chair, the following preamble and resolutions

were formally adopted:

“Whereas from information deemed reliable that Federal troops

were on the way to garrison Fort Caswell at the mouth of the Cape Fear River, which was regarded as a menace to our people and State, a portion of the citizens of Brunswick and New Hanover Counties, took possession of said Fort in order that the State for her protection, might obtain peaceable possession of the same.

Therefore, Be it---

Resolved, first, That we highly approve of the patriotic spirit and

pure motives which prompted our fellow citizens of the above

counties in their action, and that a Committee of Three be

appointed to make arrangements for presenting them with some tangible evidence of our regard.

Resolved, second, That in the prompt evacuation of said Fort

by order of the Governor of North Carolina, they have proved themselves to be good and loyal citizens of the Old North State.

Resolved, three, That the dilatory action of our Legislature

in calling a Convention may, in view of the imminent

danger now threatening us and our sister Southern

States, force the State into revolution, and this can

only be secured by the speedy action of the Legislature

in trusting this great question with the people, by doing

which and by placing the State in a proper condition

for defense, they may make secession peaceable.”

B.W. Beery, Chairman, James O. Smith, Secretary”

Benjamin W. Beery

Public Safety Committees and Resolutions:

North Carolinians historically were no strangers to a danger of invasion,

as in 1774 and 1775 eighteen counties and four towns set up safety

or vigilance committees. The committee members were usually chosen

by mass meetings of citizens, and their goal was to direct the effective defense of the city and region with militia, weapons and supplies in

the event of conflict. Predictably, these committees were

denounced by Royal Governor Josiah Martin as “motley mobs”

and “promoters of sedition.”

The Wilmington-New Hanover Safety Committee even regulated trade

to the extent of seizing British cargoes, fixing the price of imported goods and urging all merchants to not sell or export gunpowder. It also called upon all householders in Wilmington to sign an agreement not to trade

with the British nor allow their slave ships to enter the harbor. The

Halifax County Committee resolved to have no more dealings with

Loyalist merchants; and Tryon County’s Committee denounced the “barbarous and bloody actions committed by British troops on our American brethren near Boston.”

By the late 1850’s, many North Carolina counties were calling meetings of their citizens “to take into consideration the wicked projects of the Northern abolitionists and fanatics…and counteract the horrid evils which they are meditating against the South.”

Sampson County adopted resolutions calling for a commercial embargo against the North and inflicting the death penalty for anyone circulating incendiary publications that would incite race war. North Carolinians were very familiar with the butchery committed in Virginia by Nat Turner and

his murderous band in 1831, and rightly blamed this on the Northern abolition fanatics.

As early as 1857, the Asheville News had called for a suspension of trade with the North, maintaining that the only way to stop the infernal whining

of Northern abolitionists is to cut off the supplies on which they grow fat. Let us trade at home, drink at home, travel for business and pleasure in

the South; learn to supply each other’s wants and to rely on ourselves.”

At a public meeting in Palmyra of citizens from Halifax, Martin and Edgecombe Counties on November 15, 1860, it was resolved that

“It is the sense of this meeting…that in the event Alabama and Mississippi join South Carolina and Georgia in a secession movement, we favor the withdrawal of North Carolina from the Federal Union.”

On November 25, the report of a Sampson County citizens’ meeting

held at Clinton was sent to Senator Thomas J. Faison and expressed

“a strong belief in State sovereignty and the right of a State to secede,

when a majority of the people in convention agree that there has been

a violation of the federal contract.”

In nearby Whiteville on December 21, “over two hundred persons,

Whigs as well as Democrats,” met in the courthouse. Local leader

John Meares “was called out and made a good and patriotic appeal to

his fellowmen in favor of the Union.” The resolutions committee offered

the resolution that “Every effort was urged to preserve the Union,” and

that the existing state of affairs between North and south should be resolved through prudence, moderation and patriotism. The committee expressed “opposition to immediate and separate secession” at that time.

A December 28th, a letter in the pro-Union Fayetteville Observer

stated that “We are now for the Union as it is. Some difference of

opinion as to the guarantees we ought to insist upon. If there is cause

for disunion now, it has existed for eight years. But as the question is

now placed upon us it ought to be settled now and forever, but let

reason and forbearance prevail…”

To demonstrate the severity with which Wilmington’s Safety (or vigilance) Committee operated, visiting British newspaperman William Howard Russell was denied access to the telegraph by Vigilance Committees who suspected him as a spy in the employ of Northern radicals as he travelled through the city enroute to Charleston on April 16th and 17th.

William Howard Russell

Ada Amelia Costin’s diary mentions the “Committee of Safety”

requesting “the ladies of Wilmington to meet at the Town Hall…on Wednesday afternoon at 5 o’clock to devise ways and means of

providing [for] destitute soldiers at the forts [Johnston and Caswell]

with necessary articles of clothing."

Why Secession?

Most Southern statesmen and military-trained leaders in the South (and the North) understood proper State and Federal relations

from prominent constitutional scholars like William Rawle, who

also authored West Point’s text on constitutional law (used there

from 1825-1840). Rawle held that “the secession of a State depends on the will of the people of that State,” and if the will of the people

in convention assembled deemed a change in government was desired, no power outside the State could alter this---the essence

of Jefferson’s Declaration of Independence.

With Rawle’s sound interpretation of the Founders’ intent well ingrained, every Southern State would follow Rawle’s legalistic

and ritual outline for the solemn withdrawal of a State from the

union each had voluntarily acceded to, done with the consent of

the governed, in convention assembled. This was the common

view of Americans in the 1850’s.

Interestingly, New York City was also considering secession as well

in January 1861 as Mayor Fernando Wood addressed the Common Council on the national troubles and the new republic of States forming to the South. He recommended that New York secede and become a “free city” and foresaw new republics in the Western and Pacific States, something that Thomas Jefferson predicted earlier.

The Washington Peace Congress:

Seeking “to effect an honorable and amicable adjustment” of the sectional difficulties “on the basis of the Crittenden Resolutions as modified by the legislature of Virginia,” North Carolina sent five representatives to the Peace Commission that assembled in Washington in early February 1861. Among the five was respected Wilmington attorney George Davis, whose bronze memorial statue now stands at the downtown intersection of

Market and Third Streets.

Geroge Davis of Wilmington

The Peace Congress sat in closed session trying to find solutions to the secession crisis which already saw several States leave the Union, but concluded without finding a reasonable compromise between the sections.

The pro-secession Wilmington Journal of 21 February opined that the seceding States would not accept the Crittenden compromise, stating that “it is too late in the day to talk about compromises…The border Southern States must decide to which Confederacy they will attach themselves…There can be no half-way course now.”

The Wilmington Daily Journal of March 4 reported that:

“George Davis, Esq., addressed his fellow-citizens on last Saturday, March 2, at the Thalian Hall in reference to the proceedings of the late Peace Congress, of which he was a member…the hall was

densely crowded by an eager and attentive audience.

Mr. Davis said he had gone to the Peace Congress to exhaust every honorable means to obtain a fair, an honorable, and a final

settlement of existing difficulties. He had done so to the best of

his ability, and had been unsuccessful, for he could never accept

the plan adopted by the Peace Congress as consistent with the

rights, the interests, or the dignity of North Carolina.”

Lincoln actually visited the Peace Conference while in session though he would not discuss any peace initiatives. New York merchant William E. Dodge said blunt to him: “Then you will yield to the just demands of the South…You will not go to war on account of slavery?” Lincoln

responded vaguely: “I do not know that I understand your meaning,

Mr. Dodge. Nor do I know what acts or opinions may be in the future---

I will defend the Constitution as it is.”

The Peace Conference’s failure was widely attributed to Radical Republican insistence on its members rejecting any compromise with the States of the South. At this same time, Lincoln’s incoming Secretary of Treasury Salmon Chase openly declared that the Northern States “never would fulfill their obligations under the Constitution in the matter of fugitive slaves.” This statement made many old time Southern Whigs realize that there was but one alternative, and that was to quit the Union as the only way of saving the Constitution of the Founders.

Up in Wilson in mid-March, a Southern Rights meeting at the county courthouse resolved that it was North Carolina’s duty, as well as every other [Southern] State, “to detach itself from the old confederation whose constitution has been violated by a majority

of the States composing it…and join the brotherhood of the South.”

The Onset of War, Cape Fears Forts Occupied Again:

North Carolinians watched with interest as events unfolded in South Carolina, and immediately after Fort Sumter fell, Governor Ellis replied

to the Secretary of War’s request for two regiments to invade

South Carolina with the following:

“I regard the levy of troops made by the administration for the purpose of subjugating the States of the South as in violation of the Constitution and a gross usurpation of power. I can be no party to this wicked violation of the laws of the country, and to this war upon the liberties of a free people. You can get no troops from North Carolina.”

The Excitement in Wilmington:

Sprunt’s Chronicles of the Cape Fear relates the response to Lincoln’s

call for 75,000 volunteers to invade South Carolina after Fort Sumter:

“the whole of the Cape Fear section was fired, and with scarcely an exception looked upon secession and war as the inevitable outcome.

Virginia seceded from the Union on April 17th, as did Arkansas on

May 6th. On the following day in Nashville, Tennessee declared independence from the United States and joined the Confederacy.

Governor Ellis did not wait for North Carolina’s official secession to put

the State in a strong defensive footing. The Legislature was called into special session on May 1st, prior to which Governor Ellis directed the seizure of forts, arsenals and other federal property in the State.

Fort Macon at Beaufort was held by Captain Josiah Pender; The

formation of military companies from across North Carolina were

offered to Governor Ellis, including Col. Alexander Murchison’s

large company of free blacks and slaves from Cumberland county,

nearly 200 strong.

On April 13th, Ellis telegraphed James Fulton at Wilmington to

“Tell the Troops to await further orders, hold themselves ready to

move at shortest notice.” On April 15th Colonel Cantwell was

telegraphed from Goldsboro:

“I have recd the following---Hon. S.J. Person---

Communicate orders to military of Wilmington to take

forts Caswell and Johnston without delay & hold them

till further orders against all comers. Signed, J.W. Ellis.

I will be down at 7 o’clock & issue in his name necessary orders---Notify the Captains. Answer. Sam’l J. Person.”

The Wilmington Daily Journal of April 15th announced from

Headquarters 30th Regiment, North Carolina Militia:

“The Officers and command of the Wilmington Light Infantry, German Volunteers, & Wilmington Rifle Guards, are hereby

ordered to notify their respective commands to assemble in

front of the Carolina Hotel at (blank) O’Clock fully armed

and equipped, this afternoon. By Order, Col. Jno. L. Cantwell.

Jas. D. Radcliffe, Adgt.”

Hanke Vollers of Wilmington's German Volunteers

Colonel Cantwell and his 30th North Carolina Militia on April 16th:

“to take Forts Caswell and Johnston without delay, and hold them

until further orders against all comers.” Cantwell left for the forts

with Captain William Lord DeRossett’s Wilmington Light Infantry

(WLI); Captain Cornehlson’s German Volunteers, Captain

Oliver Pendleton Mears Wilmington Rifle Guards, and the

Cape Fear Artillery of Captain John J. Hedrick (under Captain

James Stevenson as Hedrick was in Raleigh obtaining supplies).

Captain James M. Stevenson

The Wilmington Riflemen under the command of Captain M.M.

Hankins was held in reserve and guarded the city.

Cantwell’s force left the Market Street dock aboard the steamer

W.W. Harllee with the transport schooner Dolphin in tow.

Arriving at Fort Johnston at 4PM, Sergeant Reilly surrendered

the post to Cantwell under protest, which was then occupied by

the Cape Fear Artillery; and Sergeant Walker surrendered

Fort Caswell at 6:20PM to the control of Cantwell’s remaining

forces. Walker was placed in close confinement after “repeated

attempts to communicate with his government.” The US Army

sergeants and their families were transported to nearby

Smithville where Cantwell’s quartermaster was ordered

to provide them with temporary quarters.

Now under local military control, the forts were prepared for

active and effective defense with guns mounted and expanded

fortifications. In his official report of 17 April, Colonel Cantwell

noted that seven 6-Pounder cannon were found dismounted

and stored at Fort Johnson, which were then placed in a new

battery under the direction of Major James D. Radcliffe. At

Fort Caswell, Cantwell reported “I find this fortification in

a dismantled, and almost defenceless condition, there being

but two Guns mounted (their carriages being unserviceable)

and no other carriages to be had within the limits of the State

so far as I am informed.”

Captain DeRossett’s WLI would soon be detached for work on

a new battery at Confederate Point and under the direction of

Captain Charles Pattison Bolles. This would be Battery Bolles,

and would grow into the mammoth earthen Fort Fisher.

Col. Cantwell would hold command of Fort Caswell until

transferred on July 20, 1861.

Capt. Charles P. Bolles

North Carolina Reclaims Its Independence:

The legislature set May 13th as election day for delegates to a State convention that would convene at 11AM on May 20th, the very day

when, in 1775, North Carolina revolutionaries had signed the

Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence, and declaring themselves a

free and independent people. In precipitating war with North Carolina,

the Lincoln regime had already begun blockading its coast---

an act of war---even before the legislature had convened.

This left little to discuss.

On May 20th, 122 delegates filed into the southern wing of the State Capitol to decide whether The Old North State would join 10 other Southern States already out of the old Union. With the galleries

crammed with onlookers, the delegates argued the merits of leaving the union or staying a member despite the threatening federal agent.

The April 17th secession of Virginia caused even staunch Unionists in

North Carolina to accept the inevitability of a break with Washington,

and debate ended at 6PM when by unanimous vote, the convention adopted an Ordinance of Secession penned and presented by Burton Craige of Salisbury at the request of Governor Ellis. Craige was a strong Southern rights advocate as was part of the 1860 Goldsboro convention

of the Southern Rights party which called for North Carolina’s secession.

Though rejecting a lengthy document which enumerated the reasons and justifications for North Carolina’s sovereign action, including Lincoln’s unconstitutional and coercive actions against the States, Craige’s ordinance simply repealed the one in 1789 by which the

State had voluntarily joined the second federated union, the first

being the Articles of Confederation.

Immediately after passage of the Ordinance, Major Graham Davee,

private secretary to Governor Ellis, threw open a window on the west

side of the building and related the news to Ellis Artillery Captain

Stephen Dodson Ramseur. One hundred cadenced discharges marked

the occasion of North Carolina reclaiming her independence; and this

was followed by a ten gun salute to the other independent States.

Within a short time it was announced that the convention had adopted

the Constitution of the Confederate States, whereupon a twenty-gun

salute was commenced.

Stephen Dodson Ramseur

May 20th was a much-revered date in North Carolina---Ada Amelia’s Diary entry of Tuesday, May 21st, 1861 mentions that “the centenary celebration is near at hand. It is likely to be hereafter marked by a still

more solemn and important event in the history of the State. It will be known, we trust, as the anniversary not only of the first, but of the second and crowning declaration and act of independence for the old State.”

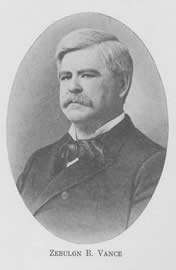

Zebulon Vance on Lincoln’s Call For Troops:

“I was canvassing for the Union with all my strength; I was addressing a large and excited crowd, large numbers of whom were armed, and literally had my hand extended upward in pleading

for peace and the Union of our Fathers, when the telegraphic

news was announced of the firing on Sumter and the President’s

call for 75,000 volunteers.

When my hand came down from that impassioned gesticulation, it

fell slowly and sadly by the side of a secessionist. I immediately,

with altered voice and manner, called upon the assembled multitude to volunteer not to fight against, but for South Carolina. I said, if

war must come, I preferred to be with my own people. if we had to shed blood I preferred to shed Northern rather than Southern blood.

If we had to slay I had rather slay strangers than my own kindred

and neighbors; and that it was better, whether right or wrong, that communities and States should get together and face the horrors

of war in a body---sharing a common fate, rather than endure unspeakable calamities of internecine strife.”

Zebulon Vance

Jonathan Worth

North Carolina Driven From the Union:

Future governor, Quaker and avid Unionist Jonathan Worth believed

that his State was driven out of the Union by the actions of the

Lincoln administration, which was trying to force North Carolinians to

not only violate the US Constitution, but also wage war on a

neighboring State. On May 30th, he wrote:

“We are in the midst of war and revolution. North Carolina would have stood by the Union but for the conduct of the national administration which for folly and simplicity exceeds anything in modern history.”

Writing on December 7, 1861, Worth concluded:

“This State is a unit against the Lincoln Government. It is one great military camp. Some then thousand troops are in the field. The old Union men are as determined as the original secessionists. The State is totally alienated from the Lincoln Government and will fight to extermination before they will reunite with the North.”

Endnote:

North Carolina’s Ordinance of Secession---May 20th, 1861

An Ordinance to dissolve the union between the State of North Carolina and the other States united with her, under the compact of government entitled "The Constitution of the United States."

We, the people of the State of North Carolina in convention assembled,

do declare and ordain, and it is hereby declared and ordained, That t

he ordinance adopted by the State of North Carolina in the convention

of 1789, whereby the Constitution of the United States was ratified

and adopted, and also all acts and parts of acts of the General Assembly ratifying and adopting amendments to the said Constitution, are hereby repealed, rescinded, and abrogated.

We do further declare and ordain, That the union now subsisting

between the State of North Carolina and the other States, under the

title of the United States of America, is hereby dissolved, and that the

State of North Carolina is in full possession and exercise of all those

rights of sovereignty which belong and appertain to a free and

independent State.

Done in convention at the city of Raleigh, this the 20th day of May,

in the year of our Lord 1861, and in the eighty-fifth year of

the independence of said State.

Sources:

The Civil War in North Carolina, John G. Barrett, UNC Press, 1963

Chronicles of the Cape Fear, J. Sprunt, Edwards & Broughton, 1916

The Heart of Confederate Appalachia, Inscoe, UNC Press, 2000

North Carolina in 1861, James H. Boykin, Bookman Associates, 1961

North Carolina, A History, William S. Powell, W.W. Norton, 1977

Thomas Lanier Clingman, Thomas Jeffrey, UGA Press, 1998

North Carolina, Lefler & Newsome, UNC Press, 1954

William Howard Russell’s Civil War, M. Crawford, UGA Press, 1992

Stephen Dodson Ramseur, Gary Gallagher, UNC Press, 1985

Dictionary of NC Biography, William S. Powell

Antebellum North Carolina, Guion Griffis Johnson, UNC Press, 1937

Confederate Operations in Canada and New York, Headley, 1906

Wilmington During the Civil War, McEachern, V-I, 1861, UNCW SC

©2006 Cape Fear Historical Institute