Mission Statement:

"To advance through research, education and symposia, an increased public awareness of the Cape Fear region's unique history."

Wilmington's 1898 Racial Conflict

"There are often two sides to a story, but always one set of facts.

The goal of an historian is to transmit those facts honestly

and without bias."

The following transcription is provided to help better understand the

unsettled political climate that helped cause the racial conflict of

November, 1898 in the city of Wilmington. The conflict is also

known as the "Wilmington Race Riot," "Wilmington Race Revolution," and the "Wilmington Rebellion."

This account was published 40 years after the event.

1898 Wilmington Race Riot

Pictorial and Historical New Hanover County and Wilmington

North Carolina - 1723-1938

Edited, Complied and Published by William Lord deRosset,

Wilmington, N.C. 1938

The Wilmington Race Revolution:

The True Story from Official Records

The Wilmington Race Revolution, November 10th, 1898, was the

direct result of ill-advice given Negroes by unprincipled white

Republican leaders. This scurrilous influence, supplemented with recognition given Negroes, through minor political offices such

as magistrates, police duties, etc., had made the darkies impudent,

and insolent. The situation finally developed to the point where

white women and children were being insulted, pushed off the

sidewalks into gutters.

The racial break came at the time mentioned above. As a result,

within 48 hours, it resulted in the white race asserting itself and

regaining absolute control of the municipal and county governments.

The conflict was the direct outcome of the general causes outlined

in the opening paragraph. The principal and motivating final cause,

combine with the general insolence and overbearing attitude of the

Negro race, following bad counsel which they received and followed,

was a diabolical and defamatory editorial. This appeared in a Negro

daily owned and edited by a contemptible Negro named F.L Manly.

This defamatory editorial was as follows, published under date of

August 18, 1898:

“Poor white men are careless in the matter of protecting their

women. Especially on the farms. They are careless of their conduct

toward them. Our experience among poor white people in the

country teaches us that women of that race are not more particular

in the matter of clandestine meetings with colored men than the

white men with colored women. Meetings of this kind go on for

some time until the woman’s infatuation or the man’s boldness,

bring attention to them, and the man is lynched for rape. Every

Negro lynched is called ‘a big burly black brute.’ In fact, many

of those who have been thus dealt with had white men for their

fathers, and were not only not ‘black’ and ‘burly,’ but were

sufficiently attractive for white girls of culture and refinement

to fall in love with them, as is very well known to all.”

As indicated, the above defamatory editorial brought the situation

to a climax. The result was that within 48 hours (when the break

came about a month following publication of the editorial) the white

men of the city rose in their wrath and indignation. They overthrew

the then-existing radical, Republican Government and drove the

majority of the Negroes’ white leaders from the city.

In a review of this nature, brevity, as a matter of course, is essential.

For this reason, only the high spots which led to a restoration in Wilmington, of a white man’s government for white people,

can be set forth.

While the cumulative causes had resulted from a number of years’ misgovernment in the state, the county, and the city, the fact is that

for a year previous to the break, the white men of Wilmington realized

that they had to band together to protect their homes. Colonel Roger Moore, a brave and distinguished officer of the Confederate Army

in command of the Third North Carolina Cavalry, by popular acclaim

had been placed in entire charge by his fellow citizens. They had

confidence in his integrity, his coolness and discretion as a leader.

Capt. Walter G. MacRae and Dr. J.E. Matthews were selected

as Lieutenants.

Colonel Roger Moore

Under Colonel Moore’s guidance the entire city was zoned and

sectioned. Each city block was patrolled throughout the night,

for twelve months or more, prior to the break.

One can well image the indignation and burning resentment which

followed publication of the infamous editorial in the Negro daily.

Within the first week of November, 1898, in the state election,

the Republican regime was swept out of power. Democracy again

reigned supreme. The determined campaign waged in New

Hanover County had been largely instrumental in influencing

other sections of the State.

On the morning of November 9th, 1898 a mass meeting of white

citizens was called in the court house of New Hanover County.

Colonel Alfred Moore Waddell who had represented this District

in Congress, was called to the chair. A lengthy set of resolutions

was read and adopted.

Alfred Moore Waddell

The gist of these resolutions was approval of the fact that a white

man’s government had been restored in the State, and that it was

the determination of the citizens present to have a similar form of Government in Wilmington, to succeed the disreputable “carpet bag” regime which had disgraced the city over a period of years. The

chief feature of the resolution was an ultimatum to the Negro

editor Manly, declaring his banishment from the city within

a period of 24 hours.

Alexander Manly

A citizen committee of 25 was appointed at the mass meeting to carry

out the spirit of the resolutions. This committee held an organization

meeting during the afternoon. In the meantime they had called a

number of Negro citizens, who were assumed to be leaders of

their race, into conference. To this delegation of Negroes was given

the ultimatum about Manly’s banishment. A reply within twelve hours

was demanded. Failure to receive such a reply, it was declared,

would be followed with definite action by the white citizens.

The reply was demanded by 7:00 A. M., of November 10th, 1898, presumably by hand, from the Negro delegation. It appeared that

an answer was drafted by the Negroes, but supposedly, was

placed in the mails.

The morning of November 10th, 1898 in Wilmington, was

characterized with a tense nervousness, which indicated subsequent startling developments. It was generally known that the reply which

had been expected from the Negro committee had not been received. Shortly after daybreak, Colonel Moore and his divisional leaders

had taken their assigned positions in different parts of the city,

where they remained until developments required their

presence elsewhere.

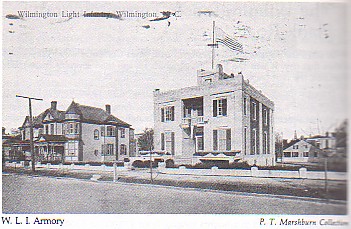

About 10:00 A.M., a crowd gathered at the Wilmington Light Infantry Armory on Market Street. Colonel Waddell was present. In response

to suggestions from members of the crowd he led the assemblage to

the neighborhood where the Negro paper was published. This building caught fire soon after the arrival of the crowd. Many joined in the

statement that the fire resulted accidentally. In any event the building

was practically destroyed, the blaze, at the same time wiping out of existence the Negro sheet which had carried the editorial defaming

and traducing the white women of the South.

When reports of the fire were received in the business district,

considerable excitement prevailed. At the corner of Front and

Walnut Streets, a large crowd of Negro laborers, who were

employed at the nearby cotton compresses, gathered. These

colored people were not intent on making trouble. The fact is,

the belief was expressed that few, if any, were armed. They were,

rather, in a state of bewilderment, wondering what had happened,

and what might eventuate.

Colonel Roger Moore, as stated above, was in command of the

entire situation. While controlling the assembled citizens at Front

and Walnut Streets, Colonel Moore was harassed by two or three excitable, white men. They told him, in effect, if he did not give the

order to fire into the Negroes on the opposite corner, that they

would do so.

Without losing his head, but with calmness and determination,

Colonel Moore responded to these hot heads. He said he had been

placed in command by his fellow citizens. Until they recalled him he intended to remain in command. He said there was no occasion at this

time for bloodshed and he certainly had no intention of having

bewildered Negroes slain in cold blood.

With this announcement, Colonel Moore told the several men who

were commanding him to give the order to fire, that he would allow

them exactly one minute in which to take their place in the ranks.

If they did not comply immediately, then he would have them arrested

and placed in jail until they cooled off. These men clearly perceived

that Colonel Moore meant exactly what he said. They then lost

no time in obeying his command.

The actual outbreak, resulting in loss of life, happened in the northern section of the city, early in the afternoon. A Negro fired into a crowd

of white men, standing near the corner of Fourth and Harnett Streets.

One white man was seriously wounded. Later, another was shot and painfully hurt. During the turbulence and conflict which resulted,

it was estimated that from seven to ten Negroes were killed.

Realizing that the aid of military forces was essential, appeal had

been made to the Governor for declaration of martial law. In the

late afternoon, this step was taken. Several companies of soldiers

from nearby points were ordered into Wilmington. Colonel Walker

Taylor, of the National Guard, was then placed in command.

With this step, the organized citizens forces which had been

functioning on a quiet basis for a year or more under the direction

of Colonel Moore, disbanded. There was no further need for their

services. Colonel Taylor was a man of discretion and good judgment,

and the situation within 48 hours was so much quieter, that the

visiting troops were ordered home.

Many Negroes, who were frightened to the point of distraction

with the turn of events, went to the woods near the city. They thought

their lives were in jeopardy. One of the last orders given by Colonel

Moore before his authority was vested in Colonel Taylor, was to

a number of white men. He told them to go in the woods, tell the

Negroes they could safely return to their homes, if they behaved themselves, and that they would be protected.

Within three days the resignations of both colored and white city

officials (representing the scum of the radical Republican rule),

had been forced. Colonel A. M. Waddell was chosen Mayor,

and an entirely new board of aldermen elected.

Under this change of administration, municipal affairs were

straightened out, and all preparations completed for a progressive

and sane policy of ruling the city, under white administration.

Assurances were given the negroes that as long as they recognized

the fact that past conditions would never again be permitted, that

their welfare would be looked after under the new condition of affairs.

A number of despicable white leaders who had largely been

responsible for the unwholesome condition of affairs, were escorted

by an outraged citizenship to trains, placed aboard cars, and ordered

never to return to Wilmington. Thus ended, what in effect might be

termed the “Wilmington Revolution.”

It was in reality merely a determined, successful movement among

white citizens to control and to manage the affairs of their municipal Government. What was true of Wilmington, as a city proved true

of North Carolina as a state. Within a comparatively short time

white supremacy again became a recognized

and acknowledged fact.

This interesting chapter in Wilmington’s development has been

recorded as an historical fact. Since the happening outlined above,

the feeling between the races has been friendly and cooperative.

The Negroes have been given the advantages of good schools,

and the same benefits from health and fire protection, etc., as

have been accorded the whites, despite the fact that probably as

much as 95 per cent of the general tax levies are paid by the

white race. Leaders of the white element are interested in the

progress and advancement of the Negroes of the community

and never turn a deaf ear to any worth suggestion or

appeal of the colored citizens.

No better conclusion to this brief history of the Wilmington Race Revolution can be offered than to relate an incident which illustrated

the humanness and fidelity of the leadership of Colonel Roger Moore.

During the afternoon of the riot, November 10th, several of the

“scalawag” white leaders of the Negroes, were captured. They

were placed in jail overnight, prior to their planned banishment

from the city. Several hundred enraged white citizens gathered in

front of the jail, as darkness approached. Threats of lynching the

prisoners were freely made. It appeared as if trouble was brewing

and that it was imminent.

Colonel Waddell, who had been chosen Mayor, went to the home

of Colonel Moore in the early evening of November 10th. He

advised Colonel Moore that threats of lynching had been heard.

He indicated that it would be ruinous for his administration, if any

such untoward event occurred. Colonel Waddell told Colonel Moore

that the latter was being appealed to, as the only man in Wilmington

who could control the crowd and prevent them from taking possible

action, which later might constitute a blot on the man of the city.

Colonel Waddell entreated Colonel Moore to go to the jail, to

control the crowd and to prevent hasty or violent action.

Colonel Moore had gotten no sleep for a period of forty-eight hours, having been on duty continuously as Commander of the citizens

protective units. Nevertheless, he told the Mayor that if he could help,

his attitude still was to prevent the citizenship from killing men who

were already in custody of the law.

Adhering to his promise, Colonel Moore immediately left his home,

went to the jail, and took his position, standing with his back to the

door. There he remained throughout the entire night. He told the

crowd that the imprisoned men were entitled to protection and

would receive it, since an aroused citizenship had already secured

control of municipal affairs. He said it would be a disgraceful reflection,

not only upon the participants but upon the city itself, if anything

happened to the prisoners, since they, already, were in custody

and would be dealt with properly.

Every persuasive and argumentative effort was put forth to have

Colonel Moore leave the jail. The men in the crowd were aware of

the fact that if he left, they could carry out their plans; that, however,

if he remained, they would have to kill him before an entrance to

the jail could be forced.

Colonel Moore thoroughly understood what the men had in mind,

and also, what would happen if he returned to his home. For these

reasons, he told the crowd frankly and positively that he intended

to hold his post at the jail door, throughout the night. He said the

only way they would enter the jail, would be after they might have

forcibly removed him fro his position.

Colonel Moore held the unbounded confidence and esteem of the citizenship as a whole and as results proved, he demonstrated the fact

that he was the one man, as selected by the Mayor, who could handle

the situation. His sound counsel and positive attitude prevailed and

the assembled crowd dispersed in the early morning hours, leaving

Colonel Moore still at his post at the jail door, and the prisoners

within the jail, terrified but unharmed.

Under the change of administration from the Republican radical

regime, which antedated Nov. 10th, 1898, to a dependable,

conservative, progressive white man’s government, the permanent

form of control until succeeding elections, properly held, was under

the following capable Board of Aldermen, serving with the Mayor:

John H. Hanby, Chas. H. Ganzer, James W. Kramer, Henry P. West, Wm. H. Sprunt, Hugh MacRae, J. A. Taylor, P. L. Bridges,

C. W. Worth, A. B. Skelding, B. F. King, F. A. Montgomery,

and C. L. Spencer.

Josh T. James was chosen City Clerk and Treasurer;

Col. Thos. W. Strange, City Attorney, Jos. H. McRee, City Surveyor,

and E.G. Parmele, Chief of Police.

©2006 Cape Fear Historical Institute